Introduction

When Stefania Marinelli contacted us approximately two years ago, also on Robert Hinshelwood’s suggestion, with a proposal to edit a monographic issue of Funzione Gamma on the subject of the therapeutic community, we felt both pleased and a bit worried. We were convinced that it would offer an important opportunity to explore a subject so dear to us, but that was also an extremely complex one. The years of efforts put forth by the on-line journal www.therapiadicomunita.org, and the practice shared by numerous friends and colleagues to whom we are bound by strong ties of affection and esteem, and who accepted our invitation to collaborate, reassured us we could offer readers an overview of the status of the therapeutic community movement at the present moment in history.

Many authors more important than we are have produced past monographic issues pertinent to their historical moments: Diego Napolitani in 1972, who edited the proceedings of a conference he organised in Milan in 1970; David H. Clark in 1973; Robert Hinshelwood and Nick Manning in 1979; Elly Jansen in 1980; Margherita Lang in 1982; Anna Ferruta, Giovanni Foresti and Enrico Pedriali who, in 1998, assembled the contributions of the more than 50 international and Italian speakers who had participated in the Mito & Realtà Conference held in Milan in June of 1996.

Times change, however, as do the aspects of psychopathology and, as the therapeutic community culture has struggled to evolve over the course of its 70-year existence (the term was coined in 1946 by Tom Main), various theoretical, methodological and technical points of view have developed. Countless writings have been published on organisational models, aspirations, doubts, problems, results, successes and failures.

Of the many conferences and publications we could cite to illustrate how the therapeutic community culture (which in Italy is known by the neologism “residential psychiatry”) put down its roots and developed, we cannot fail to foreground at least two distinctive milestones:

– Colleagues, such as Robert Hinshelwood and Kingsley Norton and many others, had long expressed to us their bewilderment at the fact that patients with very different psychopathological problems – psychosis, personality disorder, drug addiction – were co-habiting in so many institutions. When in 2004 Silvia Corbella, Raffaella Girelli and Stefania Marinelli published their work on the importance of homogeneous groups, about how these could facilitate an atmosphere of co-existence, the elaboration of problems and the attention and culture of the caregiver work group, a new chapter in residential psychiatry began. Perhaps even as yet few Italian institutions have sought to form homogeneous groups, but the volume edited by Anna Ferruta, Giovanni Foresti and Marta Vigorelli in 2012 is a broad collection of writings by friends and colleagues of Mito & Realtà on the importance that residential communities differentiate their approaches in function of patient psychopathologies, in addition to focusing on clinical-rehabilitative and organisational factors (referral and discharge procedures, the functions and importance of leadership, individual, group and family psychotherapy and external reintegration) and caregiver training.

– Giovanni Girolamo, a scholar of psychiatric epidemiology and assessment, was certainly one of those most deeply committed to the project entitled PROGRESS (begun in 2000), one of the broadest based international projects in the field of residential psychiatric assistance, and which made it possible to survey all Italian facilities, assessing 264 of these and their approximately 3,000 residents. If the study had been able to continue regularly over the years, it would certainly have offered a highly significant reading of the state of affairs in Italy. Unfortunately, instead of going forward to document the dynamics and changes in the national situation, it was suspended for lack of funding.

- A case of therapeutic engineering

In taking on the task of editing this monographic issue of Funzione Gamma, we needed a topic that could help us describe that fil rouge running through the contributions we would be asking of our friends and colleagues.

We were reminded of a topic that Robert Hinshelwood had treated at a conference in Varese in October of 1998, and that we had subsequently discussed at length with him many times over dinner and in the training meetings that he held at our therapeutic community Porto Onlus. The theme was how a social organisation that unites two such vastly different social groups as therapists and patients must and/or can be constructed.

Robert observed (Hinshelwood R., 2001) that it was simplistic to think that just because mental asylums were once large, unwieldy facilities, today it was sufficient to keep institutions small; or that, since asylums were once located on the outskirts of cities, it was now enough that they be incorporated into the social fabric. He also agreed on the fact that, as much as the term “therapeutic community” coined by Tom Main in 1946 (now distorted by the neologisms of Italian practice into “residential facilities” or, we would add, worse yet by acronyms such as S.R.P.1, S.R.P.2, S.R.P.3) is loaded with semantic value, it is equally important to build a house where many things can happen: an expression of aspects such as atmosphere, theory and technique.

Naturally, the discourse put forward by Robert Hinshelwood is much richer and more detailed than what we have summarised, but we would like to say that, with the shutdown of old asylums, new prospects and developments have come onto the horizon that are still under way, and they point to a change of orientation, paradigm, approach and civilisation.

The ambition of this issue of Funzione Gamma is, therefore, to offer a series of considerations on how those so-called “therapeutic communities” should be designed and built.

Although it seems to us that we have developed considerably in these more than 70 years, we maintain the importance of doubt and uncertainty, along with the opinion that much remains to be studied and developed.

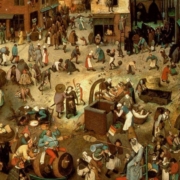

The image with which we have chosen to open is of an oil painting done in 1559 by Pieter Bruegel entitled “The Fight Between Carnival and Lent”, from the Kunshistorisches Museum of Vienna.

Scholars of this artist’s work have analysed both his proposed meditation on the human condition and also his ability to depict, without resorting to idealisation and with amiable irony, people spurred by their most problematic drives in a universe that is anything but idyllic. The only figure spared the pains of terrestrial existence is the shepherd, a recurrent figure in Bruegel’s paintings, who represents resistance and awareness, an observer facing down the world’s tempests, but who disappears in the gloomier works of the artist’s late production.

We wish to ask readers and the friends who have contributed to this issue of the journal whether the choice of this image sufficiently represents that very unusual experience of co-habiting with other problematic persons in a therapeutic community; if it can be seen as emblematic of persons in such circumstances, their struggle between mourning their past – as Antonello Correale writes – and attempting to effect change and seek a better future, with the anguish associated with repetition compulsion, and the precarious equilibrium between individual and group identity, internal and external world; and, finally, if the figure of the shepherd is suitable to representing that function that we define in contemporary terms as the leadership function.

- The old one-dimensional barycentre

In the conference Des espaces autres (of other spaces) held by Michel Foucault in Tunis, and not published in the original language until 1984, the author coined the term “heterotopia” to indicate sites “endowed with the curious property of being in relation with all the others, but in such a way as to suspend, neutralize, or invert the set of relationships designed, reflected, or mirrored by themselves”. He speaks of a long list of sites that vary widely: of the mirror in which we see ourselves but where we are not; of the cemetery as a site of union/separation between the space of the living and that of the dead; of theatres, cinemas, gardens, hotel rooms, mental asylums and prisons. Although these are places that differ profoundly, they have a sort of common denominator: a brief or long period of suspension elsewhere; of isolation from usual communication, ours or that of others; thus, a suspension of space and time, ours or that of others.

Clear in the case of mental institutions and prisons was the society’s intention to defend itself by eliminating all sources of disturbance and locating these institutions far from the centre of town.

Those who know the history of psychiatry know that it is a false generalisation to say that all asylums were conceived as nasty, badly managed, negligent places where patients were placed in isolation or beaten.

Indeed, a visit to any one of the three Italian museums of the history of psychiatry (1) shows how, in more than one case, the asylum was a system of buildings and complementary spaces that made up a veritable micro-city with physical walls and guarded gates. In addition to administrative buildings, hospital pavilions differentiated by pathology, doctors’ surgeries and staff quarters, the complexes also included communal services (chapel, library, theatre), art and occupational therapy workshops (woodworking, weaving, shoemaking, tailoring, typography and so forth), as well as green areas for gardens and farming activities.

- A new barycentre, a multidimensional array of orientations

A different approach to the social reintegration of persons with psychiatric problems gradually began to spread across Europe after the Second World War, which, in some countries more and in others less, led to the creation of a series of institutions.

If therapeutic communities, residential communities and group apartments today handle patients in a sub-acute phase but still, unfortunately, unable to go back to living with their families or to create new ones, it should be acknowledged that this has become possible as a result of having finally overcome the old stigma that condemned a person to life elsewhere.

Going back to the concept of therapeutic engineering, we have to note that it was not solely a matter of how to set up an individual institution but also of how so many institutions were to be distributed across the country.

In his research, Giovanni de Girolamo (de Girolamo ed al, 2004) illustrates the considerable development in Italian residential psychiatry but also the broad variation from Region to Region, both with regard to numbers of ‘beds’ as well as to organisational methodology. And that this variability has nothing to do with the rates of prevalence of disorders among the Regions (which are entirely similar), but exists as a result of administrative stances produced by the pseudo-scientific reasoning steered by local ‘experts’, special interests and wielders of public and private power, and the need to cut costs. Many other authors (Malinconico A., Prezioso A. 2015) have dedicated publications to the theme of the community therapy movement in Italy, its birth and development, the over- and under-estimations of it and its maledictions and misfortunes.

- The historical development of community therapy, ideological struggles and Third conditioning

In other works we have sought to perform an initial analysis of what has been a highly complex and multifaceted story both in England (Hinshelwood, 2015) and in Italy (Corulli, 2015).

The current status is as follows:

– we need a national map of the various ramifications of what is known as residential psychiatry, which would naturally have to be regularly updated, not least in order to permit citizens to exercise their right to make an informed choice, which is based on the right to information.

– there continues to be a lack of sufficient research on patient conditions at intake, at six months, at discharge and so forth.

– major university institutions and scientific communities have been absent in all aspects of the development of residential institutions.

– there are no national guidelines, which – even acknowledging the age-old dichotomy between a more psychodynamic or more socialising orientation – could outline adequate conceptual, practical and staff-related orientations with greater clarity.

To summarise, we could say that, just as we do not have a clear idea of what is available neither do we have guidelines on its appropriateness. We are sorry to have to maintain that the Ministry of Health has not been a Third in promoting evolution, and the university system has not been a Third in advancing culture and research.

Recently, during a conference on the function of outpatient centres, Giovanni de Girolamo cited Roger Penrose on the physics of the universe (Penrose, 2016) to support the idea that even in psychiatry much has been developed on the basis of Fashion, Faith and Fantasy. Three factors to which we could add, as unwelcome intruders, the struggle among ideologies, bureaucracy, the focus on cutting costs and, more recently, the Ford assembly line-like, mechanical vision of psychiatry in which there is no need to talk with a patient and compile a medical history when GAF and HoNOS assessments are enough.

It is our hope that this issue will provide readers with a reasonable conceptual key to a better understanding of the mission that distinguishes residential psychiatry.

Bibliography

Clark D.H., (1973) Social Therapy in Psychiatry, Penguin Books, Harmondworth. Ed It. (1976) Psichiatria e terapia sociale. Milano: Feltrinelli.

Corbella S., Girelli R. Marinelli S. (2004) Gruppi omogenei. Roma: Borla.

Corulli M., (2015), Appunti sul movimento delle Comunità Terapeutiche in Italia. Nascita. Sviluppi, enfatizzazioni, malefici e malesorti…, in Malinconico A., Prezioso A. (2015) Comunità Terapeutiche per la salute mentale. Milano: Franco Angeli. V. anche www.terapiadicomunita.org Anno 16, n.62, Febbraio 2016.

de Girolamo G., Picardi A., Santone G., Semisa D., Morosini P. (eds) per il Gruppo Nazionale PROGRES (2004). Le strutture residenziali e i loro ospiti: i risultati della fase 2 del progetto nazionale ‘PROGRES’. Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale Supplemento 7.

Ferruta A., Foresti G., Pedriali E., Vigorelli M, (1998) La comunità terapeutiche, Tra mito e realtà. Milano: Raffello Cortina.

Ferruta A., Foresti G. Vigorelli M, (2012) Le comunità terapeutiche, Raffaello Cortina, Milano.

Foucault M., (1984 ) Dits et écrits, Des espaces autres (conférence au Cercle d’études architecturales, 14 mars 1967), in Architecture, Mouvement, Continuité, n°5, octobre 1984. Ed. it. Eterotipie, in: Archivio Foucault, 1998. Milano: Feltrinelli.

Hinshelwood R.D., Manning N., (1979) Therapeutic Communities. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Hinshelwood R. (2001), Aspetti etici del lavoro di comunità terapeutica, Anno 1, n. 2 www.terapiadicomunità.org

Hinshelwood R. (2015), Comunità Terapeutiche “vere e proprie” e “ improprie”. Una riflessione su alcune visioni inglesi e italiane. in Malinconico A., Prezioso A. (2015) Comunità Terapeutiche per la salute mentale. Milano: Franco Angeli.

Jensen E., (1980) The Therapeutic Communities. London: Croom Helm.

Lang M., (1982) Strutture intermedie in psichiatria. Milano: Raffaello Cortina.

Malinconico A., Prezioso A. (2015) Comunità Terapeutiche per la salute mentale. Milano: Franco Angeli.

Napolitani D., (1972) Psichiatria comunitaria e socioterapia. Minerva psichiatrica e psicologica, vol 13, suppl. n. 2. L’edizione originale, arricchita da ulteriori category, è stata ripubblicata: Di Marco G., Nosè F., (2010) La clinica istituzionale in Italia. Milano: Franco Angeli.

Penrose R. (2016), Fashion, Faith and Fantasy in the New Physics of the Universe. Princeton University Press.

Notes

(1) The Lombroso Pavilion of the former San Lazzaro psychiatric hospital in Reggio Emilia, the former Santa Maria della Pietà psychiatric hospital in Rome and the San Servolo psychiatric hospital in Venice.

The Editors

Metello Corulli is Psychologist, specialized in clinical psychology. He obtained a Master in Anthropology, is analytical oriented Psychotherapist and group therapist trained in psychodrama as well. He worked for eight years at the hospital operating in the drug-addiction, endocrinology and neurology services. Founding member of Il Porto Therapeutic Community in 1983, he is chair of Il Porto since 1998. Founder and Director of Terapia di Comunità On-line Journal (www.terapiadicomunita.org) since 2001, Director of the Book Collection on Therapeutic Community, Ananke Publishing, since 2015.

Chair of Fenascop – Piedmont Area since 2013 (FENASCOP-National federation of psychosocial community facilities) and member of its scientific committee. He taught at the Schools of Specialization in Clinical Psychology of the University of Turin.

Speaker, chairman and member of scientific and administrative committees, he organised several conferences on therapeutic community and institutional life dynamics issues. He fostered and directed two Masters for Professionals Operating in the Therapeutic Community, in 2003-2004 and 2015-2016. Formerly member of scientific committee/board of Mito & Realtà Association, honorary magistrate of the Juvenile Court of Turin, presently is expert consultant of the Court of Turin.

He published several scientific papers, as monographs, book chapters, national and international journals articles, conferences acts. With Bollati Boringhieri Publishing he edited the volume Terapeutico e antiterapeutico. Cosa accade nelle comunità terapeutiche (1997) (Therapeutic and antitherapeutic. What happens in the therapeutic community.).

Email: MetelloC@altervox.it

Matteo Biaggini is Psychologist, Psychotherapist and Jungian Analytical Psychologist, full member of Italian Analytical Psychology Centre (CIPA) – Milan Institute, and full member of IAAP. From 1999 to 2015 he was deputy coordinator of the team dealing with the advanced phase of psychological treatments at “Il Porto Onlus Therapeutic Community”. Currently is in charge of the scientific and cultural activities of “Il Porto Onlus” and is the contact person for foreign colleagues and institutions as well. Editor of the online journal “Terapia di Comunità”, Member of the board of the “Mito & Realtà Association”, he’s also External Consultant at ETF – European Training Foundation. He has written papers and spoken at a number of conferences on therapeutic community and institutional life issues. He also edited and translated the italian version of the Austen Riggs Reader Treatment Resistance and Patient Authority, originally edited by Erik M. Plakun, published with Ananke-Il Porto Publishing (2015)

Email: m.biaggini@ilporto.org

Translation from Italian: Darrag Henegan